Sinology: Lessons From China

By Andy Rothman

In the ninth month of a crazy year, I thought this would be a good time to look back at the lessons we can learn from observing the Chinese economy and U.S.–China relations. In this issue of Sinology, I will focus on the takeaways from five topics: China's approach to controlling COVID-19; China's strong post-COVID economic recovery; the risks that the nature of that recovery will exacerbate China's inequality problems; Washington's misguided approach towards China, and the potential impact on innovation in America; and the mistakes Beijing is making as it tries to play a bigger role on the global stage.

Lesson 1: Taking COVID seriously saves lives

As I've written many times this year, keeping the coronavirus under control is key to any country's economic recovery. In China, there are reasons to be optimistic. In the U.S. and many other major markets, well, not so much.

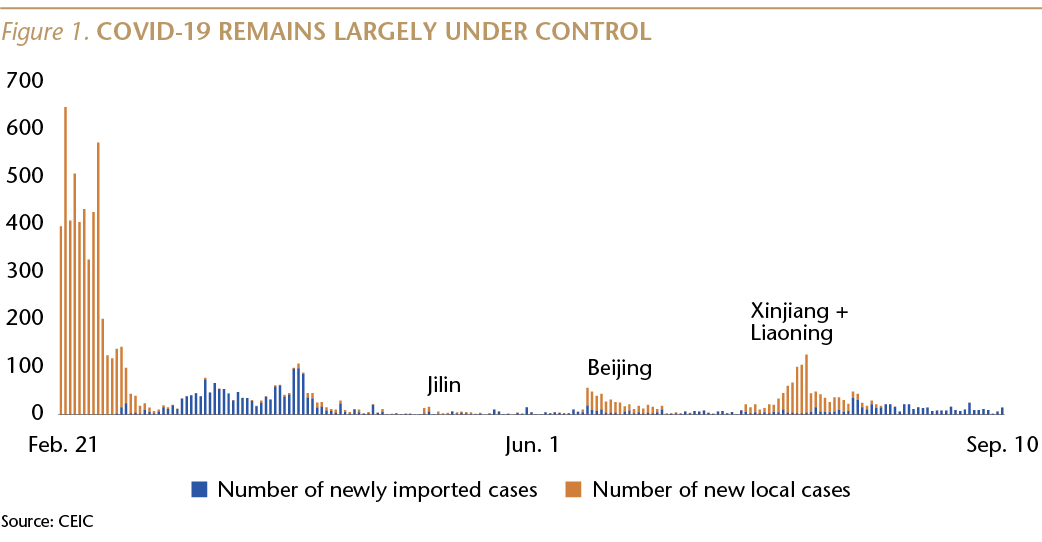

As of September 14, China had not reported a single, locally transmitted COVID case in 30 days. On September 14, there were only 142 COVID patients in Chinese hospitals, down from 655 one month earlier, and from 58,016 on the February 17 peak.

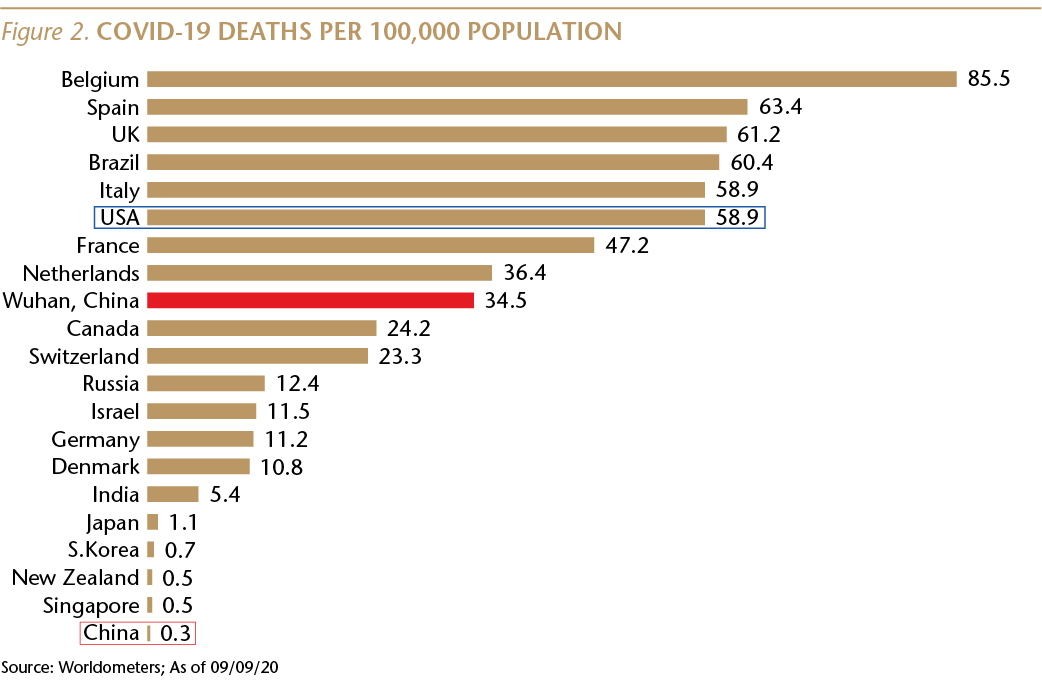

Since the pandemic began, the U.S., which has approximately 4% of the world's population, has recorded 21% of the world's COVID deaths. China, home to approximately 18% of the world's population, has recorded 0.5% of COVID deaths.

Recently, the COVID picture in the U.S. has improved, but seems to have plateaued at an unacceptably high level. In the first 12 days of September, there was a daily average of 868 COVID deaths in the U.S., or 3 deaths per 100,000 population during that period of time. (By comparison, during the month of August, the average daily number of COVID deaths was 986.) Since the pandemic began, the U.S. has recorded 59 deaths per 100,000 population.

To be sure, some of the methods used by the Chinese government to successfully combat COVID would be difficult to deploy in a democracy. My colleague Julia Zhu has written an excellent piece about her recent experience with quarantine when returning to China to visit her parents.

But other democracies have had greater success than the U.S. in controlling COVID. Canada, for example, has recorded 0.1 deaths per 100,000 population during the first 12 days of September, and 24 deaths per 100,000 population since the pandemic began.

Taiwan and South Korea took the coronavirus seriously in January, and the results are clear. Taiwan has not reported a death since May 11, and a mortality rate of 0.03 per 100,000 population. South Korea has reported only 31 deaths in the first 12 days of September, and an overall mortality rate of less than 1. Japan has reported 144 deaths this month and an overall mortality rate of 1.

I know that some investors wonder whether the Chinese government's COVID data can be trusted. I think there are two reasons to believe that since January 23—when the government shut down the city of Wuhan, where the virus was first identified, and which has a population larger than that of New York City—the Chinese government has not been deliberately falsifying its COVID data.

First, if the number of hospitalizations and deaths were significantly higher than the official statistics, we would be hearing about it on social media from the family and friends of those patients. Second, the numbers reported by China have been consistent with data from other places in the region which undertook similarly aggressive efforts to control the virus.

Lesson 2: Taking COVID seriously is key to economic recovery

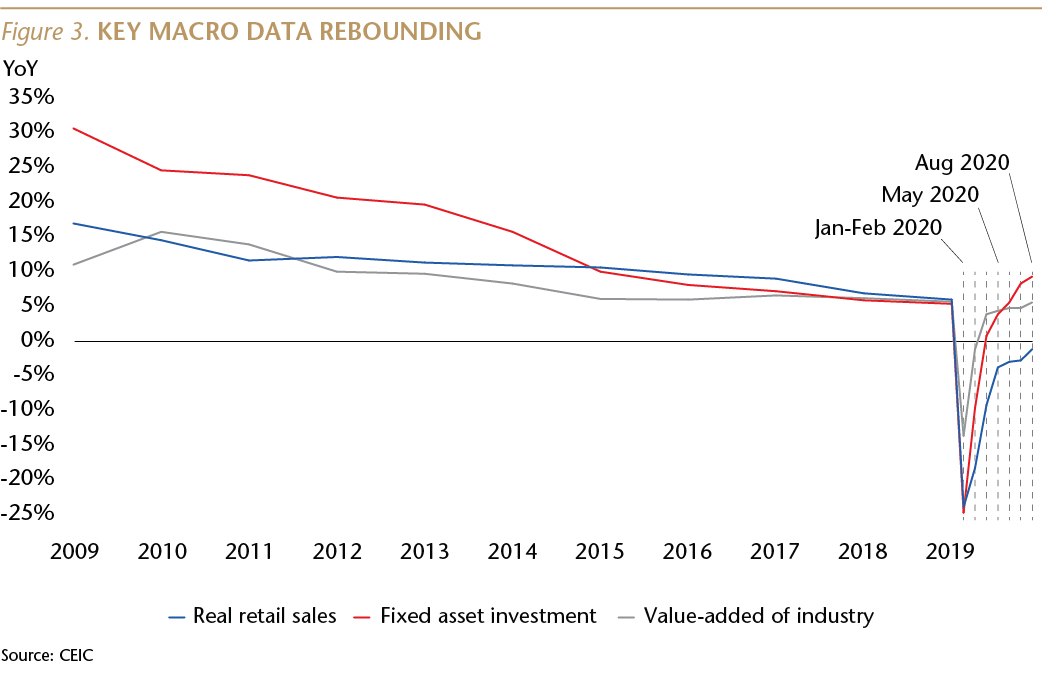

With COVID largely under control, life in China has been gradually getting back to normal since March, and August was the sixth consecutive month of a V-shaped economic recovery.

China's economy is increasingly driven by domestic demand, so it is important that consumer spending has been bouncing back. Last year was the eighth consecutive year in which the consumer and services (or tertiary) part of China's GDP was the largest part. Although consumer spending is likely to remain softer than usual until next year, on a relative basis China is likely to remain the world's best consumer story.

Traffic jams and long lines outside of popular restaurants are back. Auto sales have posted double-digit year-over-year growth for four consecutive months, and online sales of goods rose at a double-digit YoY pace in each of the last six months. New home sales have registered YoY growth, in volume terms, for four straight months, after declining by 39% YoY during the first two months of the year. Industrial production has fully recovered.

Sales at food services and drinking places are beginning to recover, but were still down 7% YoY last month, due to lingering fears many people have about gathering indoors. It is likely that this part of the economy, as well as other businesses that require customers to gather in confined spaces, will take a long time to fully recover. This is why I expect China's economic activity to return to about 80% of normal by the end of this year, with the final 20% of the recovery unlikely until after an extended period of time with very few new COVID cases in China, the global pandemic under control, or the development and widespread use of an effective vaccine.

Lesson 3: Exacerbating China's inequality problem

The Chinese economy has recovered from COVID without a dramatic government stimulus. In most respects, this is a good thing. But, the government failed to provide an adequate social safety net for many of those hit hardest by the economic impact of the coronavirus, which is likely to exacerbate the country's income inequality problem.

Very small-scale, privately owned businesses (ge ti hu) account for about 28% of non-agricultural employment, and these firms account for about three-quarters of the restaurants, bars and household-service businesses that have suffered the most from COVID.

The government doesn't appear to have done enough to help these workers survive the lockdown and the continuing reluctance of many people to patronize businesses that feel risky, despite COVID being largely under control.

In the first half of the year, net transfer revenue accounted for 18.8% of per capita income, barely changed from the 17.7% share a year ago, reflecting the minimal effort by the government to replace lost wages. In the U.S., in contrast, government social benefits accounted for 27.6% of personal income in the second quarter of this year, up sharply from a 16.6% share a year earlier.

Another way to look at it is that monthly income for China's 178 million migrant workers, who are the backbone of the sectors suffering the most from the impact of COVID, was down 6.8% YoY through the end of June, compared to a rise of 6.9% a year ago.

While not an immediate threat to economic growth or social stability, this inequality is a significant, long-term challenge.

Lesson 4: Washington's misguided approach towards China

In my view, the U.S. government's current approach towards China is misguided and almost certain to hurt, rather than help, the American economy.

The approach is misguided in part because it fails to recognize that over the past 40 years, engagement between the two countries has led to progress. Most Chinese people have a healthier and more comfortable life, and enjoy far greater personal freedom. China has supported U.S. efforts to limit the spread of nuclear weapons, and to resolve the dispute on the Korean peninsula.

While China has clearly not lived up to all of its WTO commitments, it has done enough to enable GM to sell more cars in China than in the U.S. Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, Nike enjoyed 22 consecutive quarters of double-digit revenue growth in China. And China is especially important to the U.S. semiconductor industry. Profits from sales to China help finance continued R&D by America's tech companies.

Since China joined the WTO in 2001, U.S. exports to that market were up over 500% as of 2017, compared to a 100% increase to the rest of the world. Prior to the current tariff dispute, China was the largest overseas market for American agricultural goods, up by 1,000% since they joined the WTO.

The structure of the Chinese economy has also changed for the better. When I first worked in China, in 1984, there were no private companies—everyone worked for the state. You couldn't even find a privately run restaurant. Today, almost 90% of urban employment is in small, privately owned, entrepreneurial firms.

More generally, we should recognize that it is not possible to decouple from China's economy, which last year accounted for 40% of global economic growth, larger than the combined share of global growth from the U.S., EU and Japan. Moreover, it will be very difficult for the U.S. to address global issues like climate change, nuclear proliferation and drug trafficking without cooperation from the Chinese government.

Personally, I am frustrated with the limitations of engagement in achieving the full range of U.S. objectives with the Chinese government. But I also think we all need to be clear about what has been accomplished, and realistic about whether alternative policies by the U.S. government would have achieved more, or less in the past, and are more or less likely to succeed in the future.

I'd like to discuss one example of how an approach designed to isolate or contain China is likely to backfire on the U.S. economy. The current administration's approach towards immigration and foreign students has already led to a sharp decline in issuance of student visas, and if this trend continues, it is likely to result in less innovation and less job creation in the U.S.

The U.S. Department of State reports that its issuance of student (F-1) visas to Chinese applicants declined by 29% in the government's 2019 fiscal year compared to the 2016 fiscal year. And it wasn't only Chinese students who decided to go elsewhere: over the same period, F-1 visas issued to Indian students fell by 30%, and total F-1 visa issuance declined by 23%.

A new study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research explains one reason why this trend is troubling: “immigrants appear to be highly entrepreneurial,” and “immigrants to the U.S. are also disproportionately likely to hold STEM [science, technology, engineering, mathematics] degrees.”1

The study, written by professors at the business schools at MIT, the University of Pennsylvania and Northwestern University, along with an economist at the U.S. Bureau of the Census, found that “immigrants start firms at higher rates than native-born individuals do. Second, immigrants do not simply start small firms. Rather, they tend to start more firms at every size, compared to U.S.-born individuals.”

“Overall,” the authors write, “immigration on net appears to be a net job creator in the U.S. economy when including unauthorized immigrants. . . these findings suggest that immigrant-founders not only are substantial job creators but also do not appear to create lower paying jobs.”

Immigrants are also important to American innovation. “Immigrants currently represent about 14% of the U.S. workforce but account for closer to one-quarter of U.S. patents. . . Firms with an immigrant founder are roughly 35% more likely to have a patent than firms with no immigrant founders.”

These findings are consistent with those reported in a 2019 study of U.S. Patent Office data by Stanford University researchers: “We find that over the course of their careers, immigrants are more productive than natives, as measured by number of patents, patent citations, and the economic value of these patents. Immigrant inventors also appear to facilitate the importation of foreign knowledge into United States, with immigrant inventors relying more heavily on foreign technologies and collaborating more with foreign inventors.” 2

A 2016 study published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives found that “The global migration of inventors and the resulting concentration in a handful of countries have been well documented.” Based on patent records from the World Intellectual Property Organization, the authors concluded, “The United States has received an enormous net surplus of inventors from abroad, while China and India have been major source countries.” 3

Lesson 5: Beijing too is making significant mistakes

China has clearly arrived on the global economic stage. As noted earlier, last year China accounted for 40% of global economic growth.

If the Chinese government wants a global leadership role commensurate with its economic stature, it must follow globally accepted principles, both for trade and for how it treats its own citizens.

On trade, I noted earlier that China has fulfilled many of its WTO commitments. But there are many other unmet commitments.

Over 20 years ago, the Chinese government signed the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Beijing has not yet ratified this treaty, but by signing the ICCPR the government signaled its acceptance of global best practices for governance, including the protection of rights to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; the rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly; and protection of rights for ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities. By fulfilling these commitments, the Chinese government would secure a much greater role for itself in the global community.

Andy Rothman

Investment Strategist

Matthews Asia

As of June 30, 2020, accounts managed by Matthews Asia did not hold positions in General Motors Company and NIKE, Inc.

Sources:

1 https://www.nber.org/papers/w27778?utm_campaign=ntwh&utm_medium=email&utm_source=ntwg8

2 https://web.stanford.edu/~diamondr/BDMP_2019_0709.pdf

3 https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.30.4.83

Back to Thought Leadership