Sinology: Confidence

By Andy Rothman

A China ‘Recovery’: How important is the loss of confidence within China itself?

Key Takeaways

- A recent trip to China underscored that one of many obstacles to recovery is a loss of confidence by the country's entrepreneurs and households in their government's economic and regulatory policies. This is not, however, an insurmountable challenge.

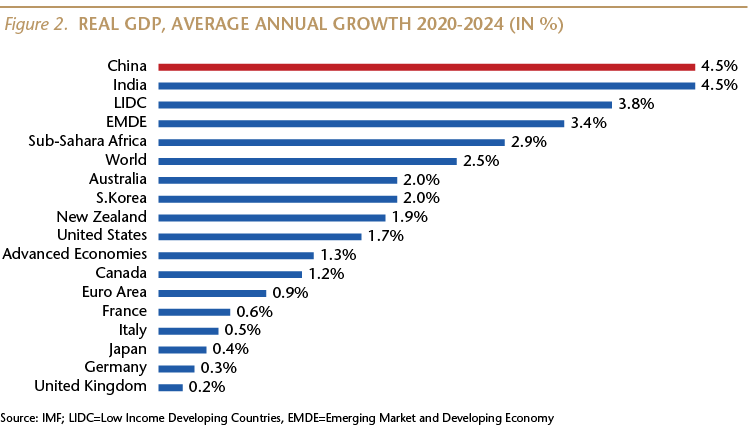

- The economy is weak but not in crisis: the IMF forecasts that this year, and in 2024, China’s GDP growth rate will be second only to India’s among major economies.

- Since July, the government has been taking a series of incremental steps designed to restore confidence. None of these measures, on their own, are sufficient to rebuild trust, but taken together they represent a pragmatic course correction that is has been lacking... although it will take time.

- The political relationship between Beijing and Washington should continue to stabilize, supporting a return of mutual confidence.

A recent trip to China underscored that a key, and perhaps underappreciated, obstacle to economic recovery is a loss of confidence by the country's entrepreneurs and households in their government's economic and regulatory policies. This is not, however, an insurmountable challenge.

The economy is weak but not in crisis: the IMF forecasts that this year, and in 2024, China’s GDP growth rate will be second only to India’s among major economies. The government has acknowledged the confidence problem and taken a series of steps to restore trust. That is not enough, but the resilience of the Chinese people and the pragmatism of the government suggest that further policy changes are coming and are likely to succeed. This process will be slower than investors would like, so the pessimistic narratives about the Chinese economy, and the domestic equity market, may not reverse immediately—but the trend is moderately positive. The political relationship between Beijing and Washington has an opportunity to stabilize, which would support a return of mutual confidence.

Confidence Within China Is Weak

Conversations with entrepreneurs during a recent trip to China make clear that their confidence has been shaken by poorly explained and poorly implemented economic and regulatory policy changes by the Chinese government. Rather than hoping for stimulus or subsidies, entrepreneurs are looking for the government to get out of their way. The property market downturn and geopolitical tensions with the U.S. were also cited as major concerns.

These worries have contributed significantly to China’s economic slowdown, but none of the entrepreneurs I spoke with were giving up. They were resilient, and were pressing ahead with business plans, while waiting for the government to make pragmatic course-corrections.

These conversations were consistent with the two fundamental elements of my framework for thinking about China: that the government, including under Xi Jinping, has largely been successful when its economic policies have been pragmatic; and that Chinese families and entrepreneurs are resilient.

History Offers Perspective

When I first visited China as a student in 1980, its per capita GDP was less than that of Afghanistan and Bangladesh, and 80% of China’s population was living below the World Bank’s poverty line. The Cultural Revolution had left the education system in tatters, with very few university graduates. Few foreign investors had interest in China, and there was little reason to believe that would change.

From 1980 through last year, however, per capita income in China rose by 148-fold, compared to a five-fold increase in the U.S. and seven-fold in the UK. In 2021, China installed more industrial robots than the rest of the world combined, and since the mid-2000s, China has consistently produced more science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) PhD graduates than the U.S.

When I returned to China in 1984 as a junior American diplomat, there were no private companies—everyone worked for the state. Today, almost 90% of urban employment is in small, privately owned, entrepreneurial firms. Private companies are responsible for China’s job, innovation and wealth creation.

All of that progress was the result of pragmatic policies that emphasized market-based reforms and de-emphasized the economic role of the state. Those policies rarely followed a consistent trajectory, but Chinese people were resilient enough to overcome obstacles and find new opportunities.

For example, between 1995 and 2001, the government took a bold step to reorient the economy, laying off 46 million state-sector workers. That was equal to sacking about 30% of today’s U.S. labor force over six years, and while painful, set the course for a private-sector dominated economy.

Current State— Signs of Improvement

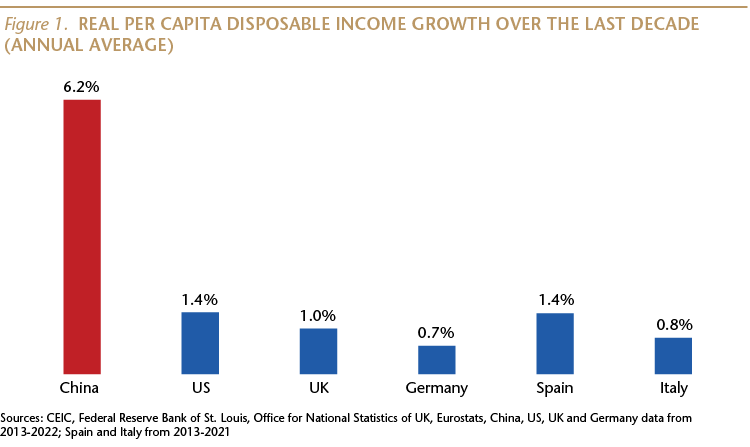

The last several quarters have been rough, but Xi Jinping’s 10-year economic track record as Communist Party chief has been pretty good. Between 2012 and 2022, China recorded average annual real (inflation-adjusted) income growth of 6.2% (vs. 1.4% in the U.S. and 1% in the UK); average annual real retail sales growth of 6.7% (vs. 4.4% in the U.S. and 2.2% in the UK); and China accounted for 33% of global economic growth during that period (vs. an 11% contribution from the U.S. and 1% from the UK).

The growth of the private sector and the rebalancing of the economy continued during the last 10 years. The share of employment and of exports accounted for by privately owned companies rose, and last year was the 11th consecutive year in which the services (tertiary) part of GDP was larger than the manufacturing and construction (secondary) part.

Economy Mixed …But Not in Crisis

I know that most media coverage portrays China as an economy in crisis. But, while the data and my on-the-ground observations reflects real weakness in some sectors, such as property, nothing signals crisis. The growth rate of the Chinese economy has slowed significantly since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, but China remains one of the world’s fastest-growing major economies. Entrepreneurs are concerned about erratic government economic and regulatory policymaking, but they clearly haven’t given up.

According to IMF data, from the start of 2020 through forecasts for 2024, China’s average annual GDP growth rate is 4.5%, fractionally faster than India, and more than twice the pace of growth in the U.S.

The consumer part of China’s economy—the largest part—has performed well recently, fueled by real per capital household income growth of 6% year-over-year (YoY) in the third quarter of this year, and that income was 21% higher than during the third quarter of pre-pandemic 2019.

Retail sales in September was 16% higher than in September 2019, and bar and restaurant sales were up 14%.

Manufacturing also recovered, with industrial value-added in September up 22% over four years ago, and electricity consumption was up 27% during that period.

In the first half of 2023, China accounted for 14.2% of global exports by value, up from a 12.8% share in 2017, before President Trump launched his trade war.

The economy has not returned to the exceptional growth rates of the pre-pandemic period, but a gradual recovery is underway.

Beijing Has Recently Acknowledged the Confidence Problem

When I was in Beijing in May of this year, few officials I met with acknowledged that confidence was weak. At that time, they pointed to strong economic data from March, and they downplayed the weaker April numbers.

Within months, however, that has changed. During the summer, officials from the government planning agency and central bank referred publicly to efforts to boost business and investor confidence, and every official I met with in October admitted that weak confidence was a key problem.

Incremental Policy Changes Designed to Boost Confidence, Starting with Rhetoric

Since July, the government has been taking a series of incremental steps designed to restore confidence. None of these measures, on their own, are sufficient to rebuild trust, but taken together they represent a pragmatic course correction that is likely to succeed . . . although it will take time.

The first step was rhetorical. Senior leaders of the Communist Party and the government issued a joint statement on “promoting the development and growth of the private economy.” The document, which serves as guidance for central and local officials, describes the private sector as “a new and strong force behind promoting the Chinese path to modernization,” and states that the Party and government want to “promote a bigger, better and stronger private sector.”

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the lead planning agency, offered unusual support for platform companies—which include e-commerce, on-line car hailing, social media and digital finance—praising them for contributing to China’s technological self-reliance, and for bolstering “the quality and efficiency of the real economy.” The agency acknowledged three major platform companies (Alibaba, Tencent and Meituan) for supporting economic development and creating jobs.

The Supreme Court then issued a document designed to “optimize the legal environment for the development of the private economy,” as a “positive signal to enhance the confidence of private entrepreneurs.”

Concrete Steps Followed

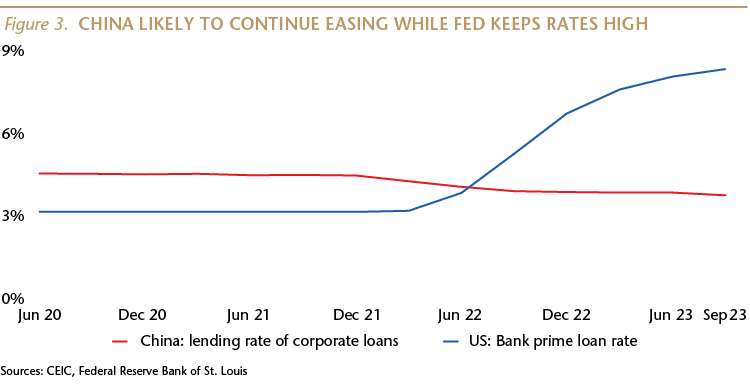

More concrete steps followed, including easing monetary policy: corporate lending rates are now at all-time lows, and are likely to remain low.

The government also rolled back a year-old cyber-security regulation, which had severely limited the ability of companies, both domestic and foreign, from transferring data out of China. This was an important change in direction by Xi, pushing back against cyber officials who previously appeared to have a free hand to promote security over business concerns, and who had gone too far. This course correction is, in my view, as significant as Xi’s decision last year to override his security team to allow the U.S. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) to audit the accounting workbooks of Chinese companies trading in New York.

Property Easing

The most significant signal of a course correction back to pragmatism to date came in the residential property sector. Given Xi’s history of concern about speculation in the residential property market and the social issues stemming from high prices, as well as his use of aggressive measures to force consolidation of the fragmented developer sector (which contributed significantly to the industry’s current problems), it is remarkable that Xi recently gave local officials the authority to lift all restrictions on new home purchases.

Xi’s decision reflects a new sense of urgency, and in the coming months I expect many local officials to take advantage of this opportunity to ease home purchase restrictions. These changes will, however, take time to have an impact on homebuyer sentiment, and it is likely that the property market will not stabilize until the second half of 2024.

(Investors should keep in mind that the property sector contribution to overall economic growth has been declining for many years as China’s housing market has matured. The compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for new home sales was 23% for the period 2001-2007, then 10% for 2008-2010, then 7% from 2011-2017, and down to 2% during 2018-2021. Despite this deceleration, and COVID, China’s GDP expanded at an average annual pace of 6.2% over the last 10 years.)

In addition to allowing city officials to relax purchase restrictions, mortgage rates have been slashed. The weighted-average mortgage rate in 2Q23 was 142 basis points (1.42%) lower than in 2Q19, and rates for existing mortgages were recently cut by an average of 73 basis points (0.73%).

It is important to recognize that, like the overall economy, the property market is weak, but not in crisis. In the first nine months of this year, new home sales on a square meter basis were equal to 70% of sales in the same period of 2019. Not great, but not a collapse.

In September, new home prices in 70 large cities were flat over a year ago, and down by 3% over two years, but were 14% higher than five years ago and 40% higher than a decade ago.

I’m not very worried about the overall structure of China’s residential property market. It’s not a bubble. Bubbles tend to be about leverage, and homeowner leverage is much lower in China than in the U.S.—a factor that helps to limit the overall impact of what is an impediment to the economy. In China, the minimum cash down payment for a new flat is 20% of the purchase price, and the average is 30% down—far from the median cash down payment of 2% ahead of the U.S. housing crisis. And, surveys tell us that about 90% of new homes in China are sold to owner-occupiers. I would like to see Beijing take two additional steps to restore homebuyer confidence.

The first would ease buyer concerns that after putting down 30% cash for a pre-sale purchase, developers might not meet their contractual obligation to complete the new flat on time. This has been a significant problem, which has made buyers wary. I’d like to see the central government create an insurance program for pre-sale down payments, similar to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which was established in 1933 to restore household trust in American banks. Developers and mortgage lenders could contribute to this Chinese fund as U.S. banks support the FDIC.

A second step I’d like to see would be for Beijing to manage effectively the rising number of privately owned developers who are in financial distress. One solution would be to instruct state-owned developers and banks to take over unfinished projects by failed private developers and complete the units as affordable housing for families who are priced out of the commercial market. This could reduce unsold inventory, especially in smaller cities, which would stabilize market prices, while starting to address the major social problem of insufficient housing for working-class families. Beijing could draw on the best practices of affordable housing programs in Singapore and Hong Kong.

An Enhanced Sense of Urgency

In recent weeks, the pace of incremental course-corrections has accelerated, suggesting a new sense of urgency among the leadership. Xi appears to understand that he needs to do more to restore confidence.

A new plan to recapitalize some local government budgets was announced and is likely to be expanded next year.

An “urban village renovation” program was announced, and an initial 162 projects have been approved, which will boost residential real estate investment.

And, Beijing took the unusual step of raising the government’s fiscal deficit ratio mid-year, to accommodate additional spending on public infrastructure. This is the first time in more than 20 years that the fiscal deficit was raised outside of the formal budget process during the March legislative session.

Initial Impact

These initial, incremental policy changes have begun to generate some progress, with sequential improvements in macro data.

New home sales on a square meter basis, for example, declined by about 12% YoY in October, less bad than the 15% decline in September.

September was the second consecutive month of double-digit YoY growth in industrial profits, compared to a YoY fall in profits a year earlier.

Retail sales in September was 16% higher than the same period in 2019, compared to a 12% expansion in August and 11% in July.

Real per capita household consumption expenditure in 3Q23 was 25% higher than the same period in 2019, compared to an 18% expansion in 2Q23 and 13% expansion in 1Q23. In each of the first three quarters of this year, household consumption growth on a YoY basis was faster than income growth, which signals an improvement in consumer confidence.

Stabilization of U.S.-China Relations Would Support Confidence

As noted earlier, during a recent trip to China, entrepreneurs told us that their confidence was shaken by poorly explained and poorly implemented changes by the government to economic and regulatory policy, including in the property sector. Most entrepreneurs also cited geopolitical tensions between Washington and Beijing as a secondary concern. Fortunately, both governments have recently taken steps to stabilize the bilateral relationship, which should help restore confidence.

The Biden administration began to recalibrate its approach to China in the spring. Treasury Secretary Yellen recently recalled that the relationship was in “a dangerous situation,” at that point, because “over two years, almost no senior-level contact had taken place.”

The recalibration to a more constructive approach—despite the domestic political risks—was signaled in an April speech by Yellen, in which she said the U.S. does not seek to decouple from China and wants a relationship that “fosters growth and innovation in both countries.”

Secretary of State Blinken continued this more constructive approach on a visit to Beijing in June, where he echoed Yellen’s comment, saying that “healthy and robust economic engagement benefits both the U.S. and China,” and that “China’s broad economic success is also in our interest.”

Blinken also reassured China on cross-Strait relations, stating, “We do not support Taiwan independence.” This has been U.S. policy for decades, but recently, senior American officials have often neglected to say this when citing the catechism of the U.S. one-China policy, which had fueled much anxiety in Beijing.

Yellen reenforced these messages during a July trip to Beijing, saying, “President Biden and I do not see the relationship between the U.S. and China through the frame of great power conflict. . . We believe it is possible to achieve an economic relationship that is mutually beneficial in the long term—one that supports growth and innovation on both sides.”

That was followed by a steady flow of high-level meetings in both capitals. Xi met with a U.S. senator and governor, while Biden welcomed China’s foreign minister to the White House, as both leaders signaled a desire to stabilize the relationship. Defense officials have begun reengaging, and consultations on a wide range of issues, including foreign policy and arms control, have been announced, and the two sides agreed to further increase direct passenger flights, which had been suspended during the pandemic.

Most importantly, China has indicated that in mid-November, Xi will travel to the U.S. for the first time since 2017, when he met with President Trump at Mar-a-Lago. The media coverage of Xi attending the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum in San Francisco, and meeting privately with Biden, should reduce significantly fears among Chinese businessmen and investors that a worsening political relationship might hinder an economic recovery.

In advance of that meeting, on November 2, Yellen gave another speech on the administration’s Asia policy, in which she said:

The United States does not seek to decouple from China. A full separation of our economies, or an approach in which countries including those in the Indo-Pacific are forced to take sides, would have significant negative global repercussions. We have no interest in such a divided world and its disastrous effects. And given the extent of economic linkages within the Indo-Pacific region and the complexity of global supply chains, it’s also simply not practical.

To be clear, I do not expect a dramatic improvement in the relationship. The administration’s goals are quite limited, as Blinken explained on July 23: “We are working to put some stability in the relationship, to put a floor under the relationship.”

But, given that I also expect Xi to continue to take a pragmatic approach to the relationship, the increase in bilateral engagement should restore some trust. While this won’t make the relationship a lot better in the near term, it should stabilize it, reducing the risk that an accident spirals into a crisis that neither side desires.

Signals Of Pragmatism and Resilience…But Still Incremental

The recent policy changes, and the gradually improving macro data, suggest that the fundamental elements of my framework for thinking about China are still valid: China’s leadership, including under Xi Jinping, has been successful when its economic policies have been pragmatic. They have made plenty of mistakes but have course-corrected to a more pragmatic path. The second element of my framework is that Chinese families and entrepreneurs are resilient.

I wish that the current policy changes would be more comprehensive, rather than incremental, and that Xi would deliver clearer signals that his government will get out of the way of entrepreneurs, but I don’t expect that to happen.

Part of the problem, according to many whom I met with in China recently, is that the leadership believes the huge stimulus deployed in response to the Global Financial Crisis was too large and left in place too long, and they don’t want to repeat that mistake. In my view, the leadership is being overly cautious at this time, but it does explain Xi’s incremental approach.

Another part of the problem is that the leadership’s political rhetoric doesn’t always align with the reality of the Chinese economy. About 90% of urban jobs are in small, privately-owned, entrepreneurial firms. But, too often, Xi speaks as if he were heading a socialist country where the majority of the workforce is employed by the state. For Chinese entrepreneurs, however, a pragmatic policy course correction is more important than the outdated political rhetoric.

The incremental nature of the course corrections means that it will take more time than we’d like for confidence to return to the point where the macro data will be strong enough for the consensus narrative about China to change from predicting collapse to acknowledging a gradual recovery to the pre-pandemic growth trajectory. That change in narrative isn’t likely to come until the middle of 2024.

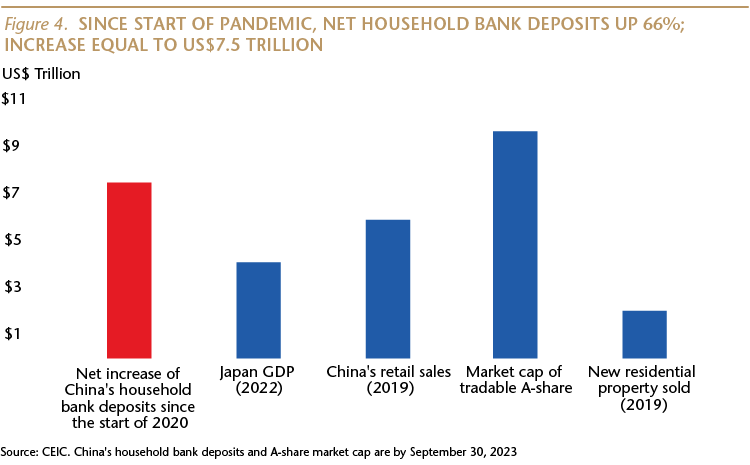

As this process unfolds, the recovery is likely to be supported by continued accommodative monetary policy and high savings. Family bank balances have increased 66% from the start of 2020, as Chinese households were in savings mode during zero-COVID. The net increase in household bank accounts is equal to US$7.5 trillion, which is greater than the GDP of Japan in 2022, and greater than the value of China’s 2019 retail sales. This could be significant fuel for a continuing consumer spending rebound, as well as a recovery in mainland equities, where domestic investors hold about 95% of the market.

Andy Rothman

Investment Strategist

Matthews Asia

Back to Thought Leadership