Sinology: China on the Road to Recovery

By Andy Rothman

China's economy was the first to suffer the consequences of fighting the novel coronavirus and is the first on the road to recovery. After an initial cover-up and more than 3,000 deaths, China appears to have brought COVID-19 under control and laid the foundation for a gradual economic recovery, although normal activity levels may not be reached until 2021. If they can prevent a second wave of coronavirus cases and continue to support the small, privately owned firms that drive job creation, China's economy could put a floor under global growth and offer opportunities for investors.

All of us at Matthews Asia send our sympathies to everyone effected by COVID-19, either directly or indirectly, and we extend our gratitude to all health care professionals, scientists and service providers who are diligently working to help and provide care to those in need around the world.

Progress towards controlling COVID-19 is key

When thinking about prospects for the Chinese economy, one of the most important factors is whether the coronavirus remains under control.

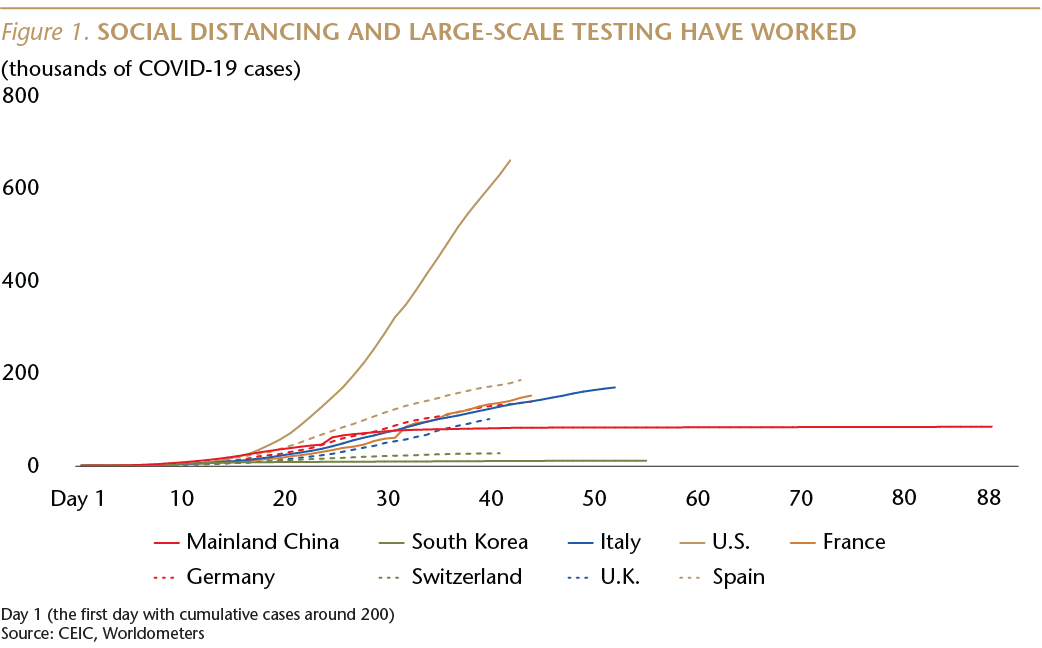

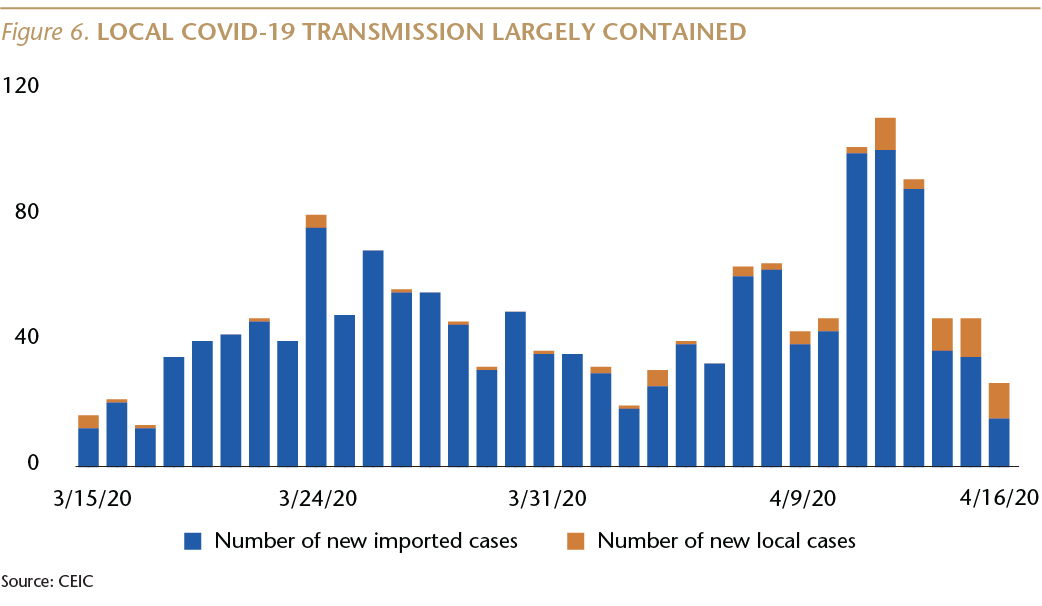

At this point, China appears to have wrestled COVID-19 into submission. Over the 15-day period ending April 15, the average number of daily new cases was 52. In contrast, there was an average of 3,859 new daily cases during the 15 days ending February 15. (During the 15 days ending on April 15, there were an average of 30,275 new daily COVID-19 cases in the U.S., and 4,888 in the U.K.)

Moreover, during the most recent 15-day period, 91% of the new cases were attributed to Chinese nationals who traveled abroad, before returning to China and having been tested at their point of entry. Local transmission appears to be under control at this time.

The number of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in China fell to 1,081 on April 16, down from a February 17 peak of 58,016. The recovery rate is now 95% nationwide, up from 15% two months ago.

China's progress in containing the virus gives hope to, and offers lessons for, the rest of the world. A study by a team of researchers from the U.K., U.S. and China found that the non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) used in China were effective—especially early case detection by testing and contact reduction (social distancing). Without those measures, “the number of COVID-19 cases would likely have shown a 67-fold increase.”

The study also concluded that delays in implementing these NPIs were costly. “If NPIs could have been conducted one week, two weeks or three weeks earlier in China, cases could have been reduced by 66%, 86% and 95%, respectively, together with significantly reducing the number of affected areas."1

Economic damage in China so far

China has just published the worst macro data since the Tang Dynasty.

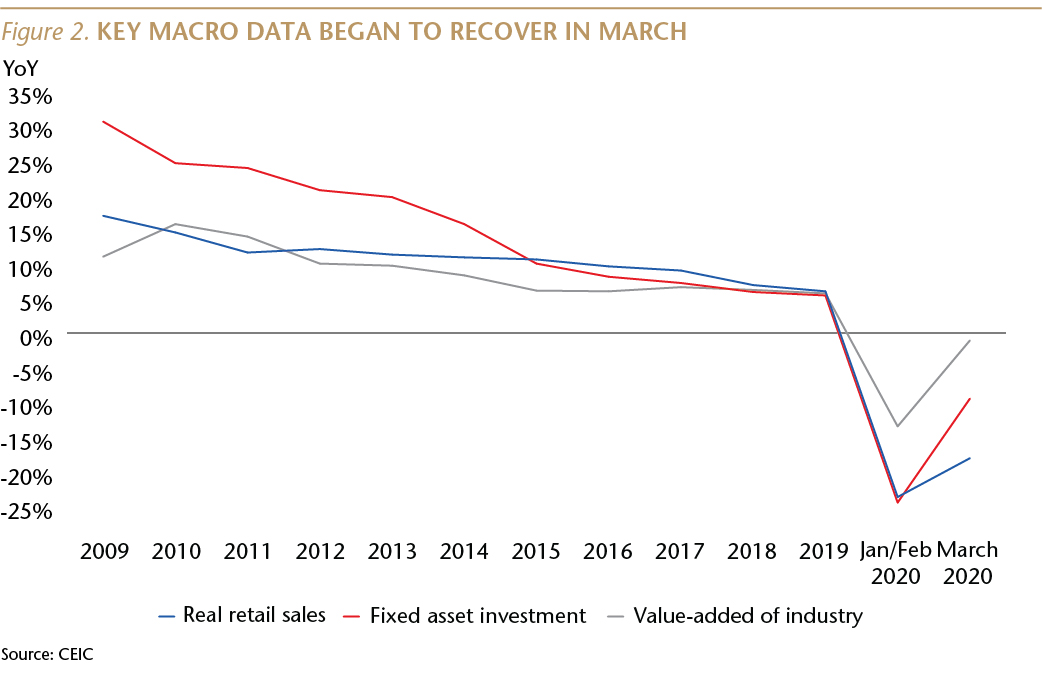

In the first quarter, retail sales declined 19% year-on-year (YoY) in nominal terms, and 21.8% YoY in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. Industrial value-added fell 8.4% YoY, and electricity generation declined 6.8% YoY. Fixed asset investment was down 16.1% YoY.

We should keep a few things in mind when looking at these dismal first quarter numbers. First, this was not a surprise. With the coronavirus raging and most shops, factories, offices and restaurants shuttered, the economy was on lockdown during much of the quarter.

The numbers were even uglier than most anticipated, which is good! First, because it reflects that China's leaders were focused primarily on fighting the virus, rather than on short-term economics. Moreover, these ugly numbers indicate that the leadership didn't fudge the data to hide the seriousness of the situation.

On the mend in March

It is important to recognize that these dismal economic numbers are not the result of structurally weak supply or demand, nor is it about structural weakness in China's financial system. The problem was that COVID-19 forced everyone to shelter in place behind closed doors. Now that the virus has been brought under control in China, those doors have gradually been opening, and life is starting to return to normal.

In fact, across most of China, life began slowly returning to normal in the second half of March, leading to signs of a nascent recovery in that month's data.

For example, the growth rate of real retail sales in March was down 18.1% YoY, far better than the 23.7% decline during the first two months of this year. Similarly, industrial value-added was down 1.1% YoY in March, compared to a 13.5% decline during the first two months. Electricity generation was down 4.6% in March, vs. an 8.2% decline in the first two months. Fixed asset investment was down 9.5% last month, an improvement from the 24.5% fall in the first two months.

The March numbers are still very weak relative to pre-COVID days. But given that the restrictions on social and commercial activities were only gradually lifted during that month, the March data does signal that China is on the road to recovery.

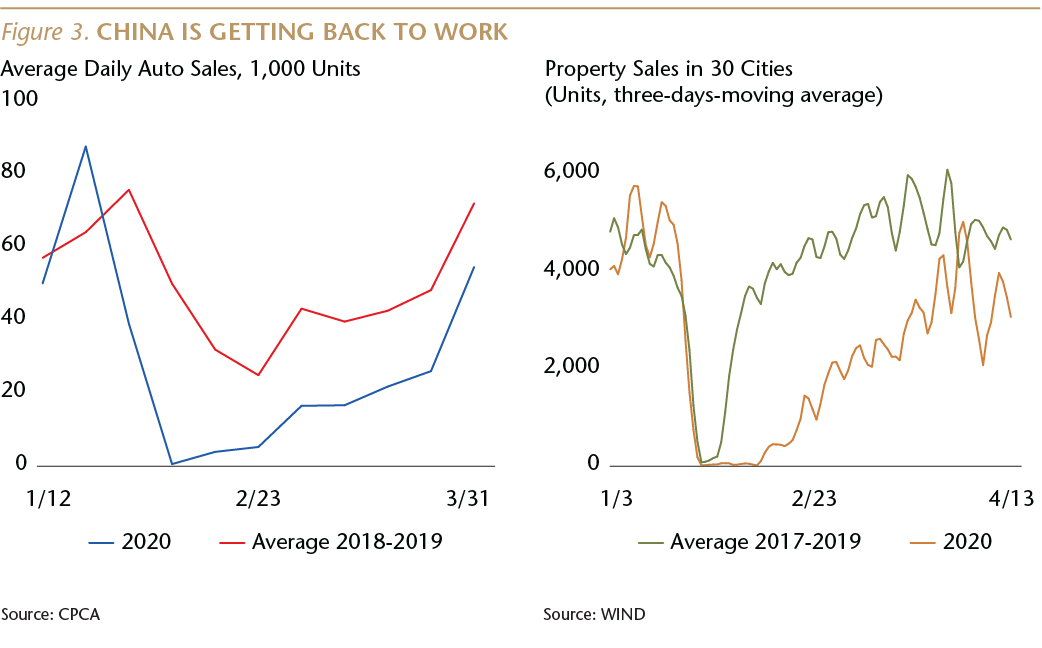

At this point, it appears that if the Zhou family was planning to buy a new car or apartment during the lockdown, they are probably still planning to do so in the coming quarters.

During the first two months of the year, passenger car sales declined 41% YoY, but they recovered to rise 14% in the second week of April. Daimler's finance chief told the Wall Street Journal that while Mercedes-Benz luxury car sales would likely continue to fall in Europe and the U.S. through April, a March rebound in their China sales should help the company post a first quarter profit. “At the end of March, our operations in China were already fully normalized, including the complete supply chain.” The finance chief said Daimler's March car sales in China were nearly the same level as a year ago, when Mercedes sold 61,913 passenger cars in China.

Residential property sales declined 39% YoY during the first two months of the year, but were down 13.8% in March. The outstanding balance of mortgages rose 15.9% in March, not far from the 18.7% pace a year ago. Assuming that middle-class income does not suffer a longer-term hit, demand for new apartments is likely to only be postponed, not eliminated. It is also worth noting that over the last 15 years, on average the first quarter accounted for only 15% of full year residential property sales, on a square meter basis.

Our colleagues on the ground in China report that shops have been reopening over the past several weeks. And on a March 24 investor call, Nike said that “roughly 80% of our 7,000 brick-and-mortar Nike owned and partner stores [in China] are now open,” and they forecast that their fourth quarter (through the end of May) revenue “will likely be roughly flat versus Q4 of fiscal year 2019.” In their third quarter, through the end of February, “Greater China revenues were down 4% following 22 consecutive quarters of double-digit growth.”

There will be sectoral differences. It will take longer for services like restaurants and entertainment to bounce back. Not because the Wang family can't afford to eat out or go to the movies, but because it will take them a while to feel safe from the virus in crowded places.

China's import growth, although still anemic, improved in March (up 2.4% YoY) compared to January and February (down 2.4%). There are signs that Xi Jinping wants to keep the trade deal signed with Trump in mid-January on track. China's first quarter imports from the U.S. fell 1.3% YoY, an improvement from the 28.3% decline in the first quarter of 2019. More importantly, there was a first quarter surge in agricultural imports from America: soybean imports rose two-fold, pork was up six-fold and cotton was up 44%, all in volume terms.

Regular readers of Sinology know that we rarely discuss GDP growth rates, as we believe that to be the least accurate and least important economic statistic in China. The other macro data discussed in this report is easier to verify and more useful for investors. But, for the record, China reported that in the first quarter, with most of the country shuttered for about seven weeks, GDP declined 6.8% YoY. On April 14, the IMF forecasted that for the full year, China's GDP is expected to rise by 1.2% YoY and then jump 9.2% in 2021. In contrast, it forecasted that in the U.S., GDP will decline 5.9% this year before rising 4.7% in 2021. The IMF's overall advanced economies forecast is similar, with a decline of 6.1% this year followed by a 4.5% rise next year. For “emerging and developing Asia,” the IMF forecasts GDP growth of 1% this year and 8.5% in 2021. In my view, the IMF's China forecast numbers are too high, but I agree with the overall trend.

Still the world's best consumer story

Last year was the eighth consecutive year in which the consumer and services (or tertiary) part of China's GDP was the largest part. Although consumer spending may remain softer than usual for all of 2020, on a relative basis China is likely to remain the world's best consumer story.

Strong income growth fueled the consumer story in the past, but that, unsurprisingly, faltered during the lockdown. Nominal per capita disposable income still rose, but by only 0.8% in 1Q20, compared to 8.7% in 1Q19 and 8.8% in 1Q18.

Very weak income growth, plus the quarantine, led household consumption spending to fall 8.2% in the first quarter, compared to an increase of 7.3% a year earlier and 7.6% two years ago. (This metric for consumer spending, which is published quarterly, includes a wider range of services compared to the retail sales data.)

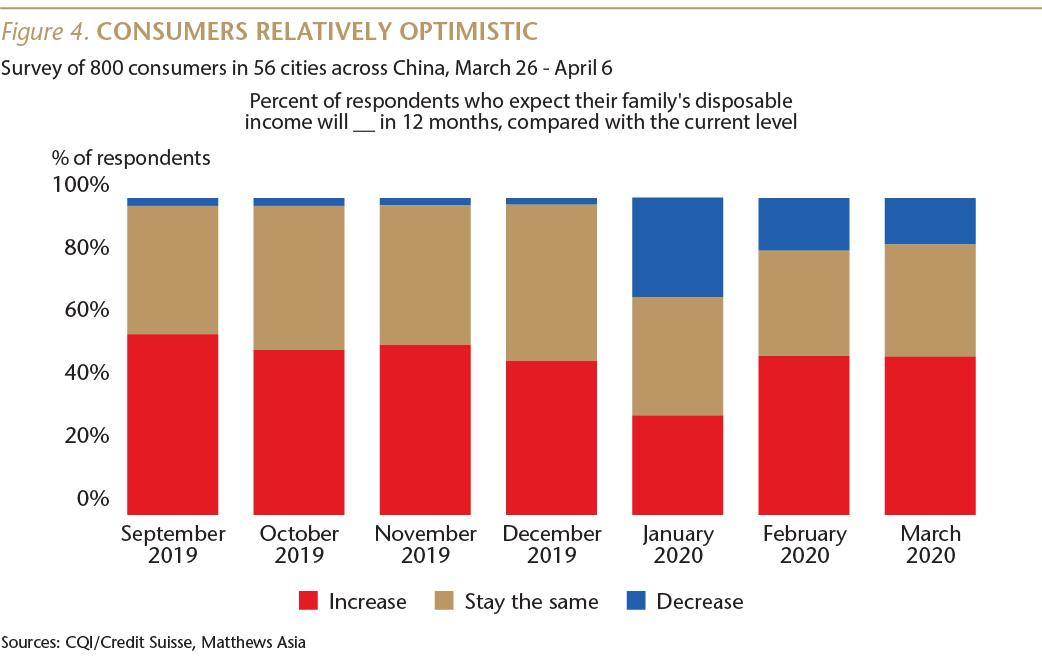

Nonetheless, Chinese consumers are relatively optimistic about the future, according to a survey conducted in 56 cities between March 26 and April 6 by the China Quantitative Insight team at Credit Suisse. Of the 800 consumers surveyed, 50% said they expect their family's disposable income will be higher in 12 months, and another 36% said it will be the same as the current level.

Coronavirus buffers

While there is no doubt that COVID-19 has hit the Chinese economy hard, there are several factors which buffer that impact, providing a foundation for what is likely to be a “U” shaped recovery.

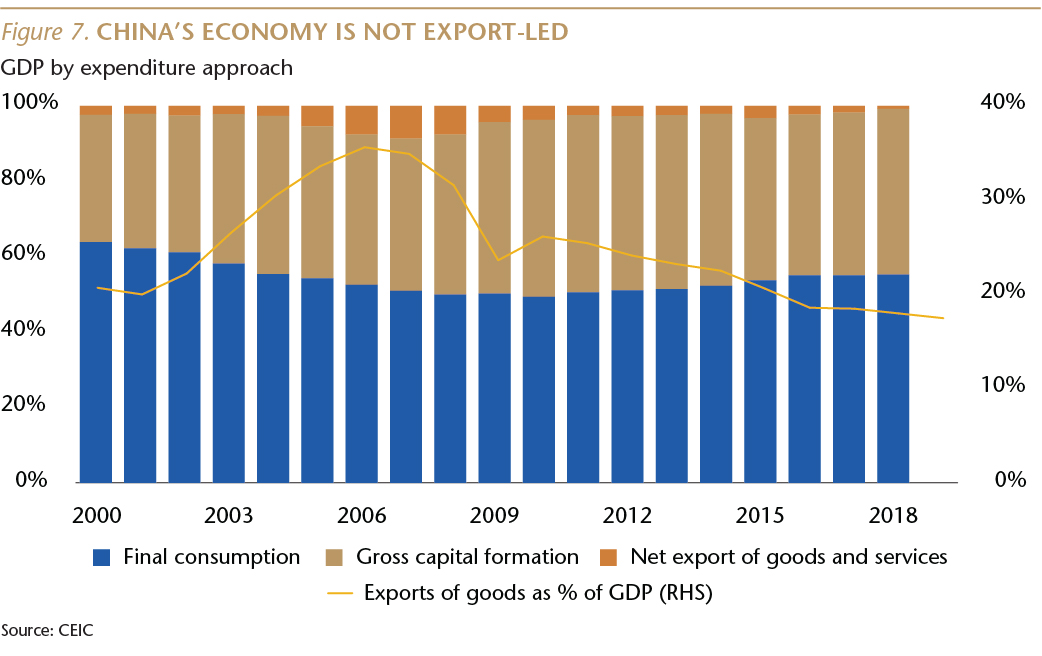

First, China's domestic demand-driven economy was healthy ahead of the arrival of the coronavirus. Last year, final consumption accounted for 58% of GDP growth, and consumption rose 9.4% YoY in the fourth quarter, up from 7.3% in the first quarter.

Income growth has been strong in recent years. Over the last decade, average annual real income growth was 8.2% in China, compared to 1.6% in the U.S.

Another buffer is that Chinese families have a very high savings rate (about 34% of disposable income for urban residents), as well as a relatively low household debt-to-GDP ratio of 54%, while household bank deposits are equal to more than 80% of GDP. To put this into context, Americans save 7.9% of their disposable income, the U.S. household debt-to-GDP ratio is 75%, while household (plus nonprofit organization) savings deposits are equal to 47% of GDP. Chinese household bank deposits rose 13% YoY in March, the same pace as a year ago.

The Chinese government has plenty of dry powder

China's central bank and finance ministry have not hefted their stimulus bazookas, preferring to take a more cautious and targeted approach to mitigating the economic impact of the coronavirus. They are keeping their large stores of powder dry, while they wait to see if the domestic demand drivers can recover under their own power.

China has taken modest steps to ensure adequate liquidity, and to reassure consumers, corporates and investors that the government has their back. In March, bank loans to household businesses (largely self-employed individuals) rose 13.3% YoY, up from 12.2% a year earlier. As noted earlier, the outstanding balance of mortgage loans rose 15.9% YoY, and other consumer loans were up 9.6%. Household demand for credit appears reasonably healthy.

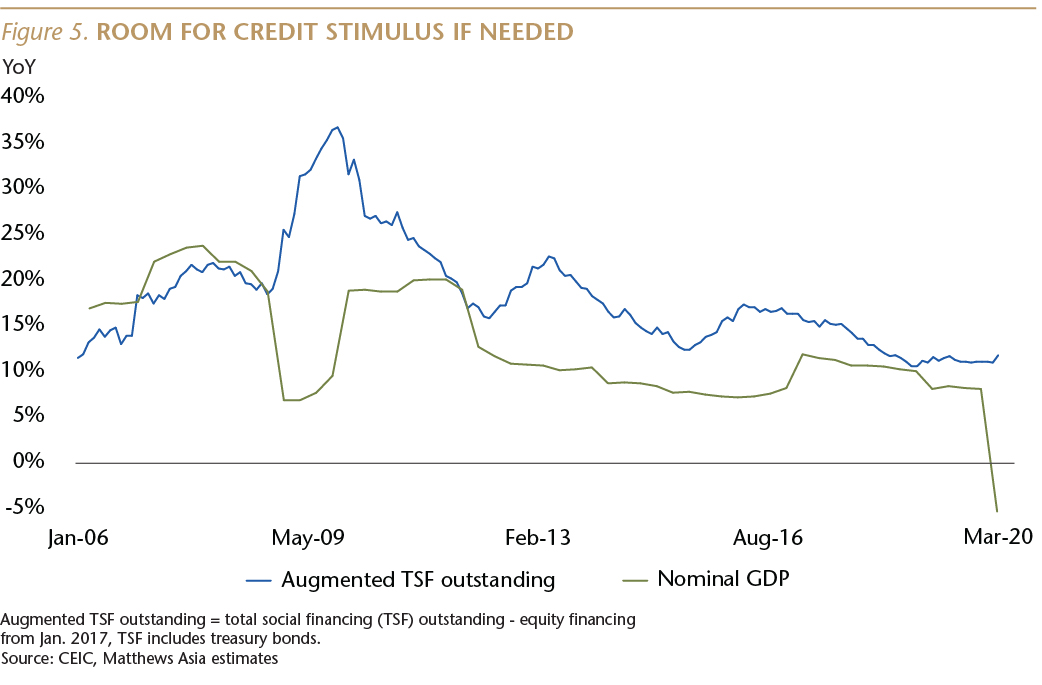

The growth rate of aggregate credit outstanding (augmented Total Social Finance) accelerated just a bit last month, to 11.6% YoY, up from 10.8% in February and 11.4% a year ago. But, given the sharp slowdown in the growth rate of nominal GDP, this does represent a material stimulus.

The government has not, however, relaxed its long-running effort to de-risk the financial system. Off-balance-sheet lending outstanding declined by 7.9% YoY in March, the 22nd consecutive month of falling shadow lending activity.

Although these monetary policy steps have been relatively modest, I think most in China believe that if it becomes necessary, their government has the political will, tools and resources to undertake the kind of large-scale stimulus that enabled China to put a floor under global growth during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). This is one reason why China's domestic stock market has fallen far less since the start of the year than many of its overseas counterparts.

Beijing's cautious approach is based on the understanding that they are still paying off the world's largest Keynesian stimulus from a decade ago. The government is also wary of relaxing restrictions on new home purchases, to avoid a sharp spike up in prices.

I have no doubt, however, that if the economic recovery now underway were to falter, or if unemployment were to cause social stress, the government would step in with bazooka-like measures. Interest rates in China are relatively high, so there is room to cut. More importantly, the growth rate of credit outstanding in the economy has been modest by Chinese standards, so there is room for the kind of dramatic credit stimulus undertaken in 2008-09, much of which could be used to ramp up infrastructure construction for the purpose of creating temporary jobs to manage rising unemployment.

There was no sign of a significant infrastructure stimulus last month, with investment in those projects down 11.1% YoY, compared to an increase of 4.5% in March of 2019. For the first quarter, infrastructure investment declined 19.7%, compared to increases of 4.4% in 1Q19, 13% in 1Q18 and 23.5% in 1Q17.

Key risks

There are two key risks on China's road to recovery. First, that the virus roars back as people in China resume their normal interactions. But, life has been slowly returning to normal in much of China over the last several weeks, and the virus has remained under control. During the 15 days ending April 15, China recorded 30 deaths due to COVID-19, compared to 343 deaths during the 15 days ending March 15 and 1,406 deaths during the 15 days ending February 15. This will remain a risk, however, in part because the virus is being brought back to China by its citizens returning from abroad. The government has been testing and quarantining arrivals in an effort to manage this risk, and on March 28 suspended entry into China by foreign nationals.

The second risk is that the smaller, privately owned companies that drive China's growth and job creation (and thus the consumption story) may have difficulty surviving long enough to see their businesses recover. These firms are not likely to have a lot of savings, or access to bank loans. Can they find a way to pay salaries and rent, and then restock inventory while waiting for normal transaction volumes to resume? The failure of a large number of small firms would result in a significant rise in unemployment.

Here, government policy will be important, and the Party has acted far more decisively than many other governments, quickly suspending collection of taxes and fees (everything from social security and unemployment to housing provident fund contributions), and encouraging state-owned landlords to do the same with rent. The 13.3% YoY increase in bank loans to household businesses last month, noted earlier, is also a reassuring sign.

Many jobs have been lost as a result of the lockdown, as in the U.S., but China has the advantage of coming off a period of strong job creation. For example, between 2013-2018 (the latest data available) employment in wholesale and retail trade in China rose 40%, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.9%. During that period in the U.S., jobs in the same sector rose by only 2.5%, for a CAGR of 0.5%.

There are two other risks that investors have raised with us, which worry me less. Stress on small private firms may result in some bankruptcies and inability to service loans, but this is very unlikely to have a significant impact on the health of China's banking system. Loans to small and micro-sized firms account for only 7.6% of total loans outstanding, and the average size of those loans is about RMB 428,000, or roughly US$ 61,000.

Finally, some investors have asked about the risk that a global recession might derail a Chinese recovery. I think this risk is low, as China is a domestic-demand driven economy. Last year, consumption accounted for almost 60% of GDP growth. The gross value of exports was equal to 17% of China's GDP, but almost 30% of those exports were processed goods for which little value was added in China. Significantly, over the last five years, net exports (the value of a country's exports minus its imports) have, on average, contributed zero to China's GDP growth. So while a collapse in demand for Chinese exports would be a drag on the recovery, it would likely be a modest drag.

In my view, the most likely scenario is that in the coming quarters China's domestic-demand driven economy will rebound, enabling its economy to put a floor under global growth (as during the GFC) and offer an opportunity to investors. China is likely to continue to account for about one-third of global economic growth, larger than the combined share from the U.S., Europe and Japan.

Andy Rothman

Investment Strategist

Matthews Asia

1https://www.worldpop.org/events/COVID_NPI

Back to Thought Leadership